I know, I know… things have been a little dark and heavy around here lately. And I promised healing! But we’re getting there—I swear. Healing wouldn’t be necessary if there wasn’t something to heal from, and for that reason, we have to start by observing and examining—even if it isn’t pretty and feels uncomfortable.

I started by sharing my personal truth to provide a lens through which to view the abuse that’s plaguing the Democratic Party at large. But from here, we’ll start to zoom out—way out.

In two of my previous Substack posts (here and here), I’ve mentioned the term “shadow” or “shadow work,” and that’s what we’re going to dive into now.

Swiss psychologist Carl Jung coined the term “the Shadow” to refer to the unconscious aspects of the personality that do not recognize themselves. These are aspects of ourselves that we often deny, reject, and feel shame toward. As he famously said:

“Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.”

In other words: the more you avoid these pitfalls of shame and shadow, the bigger impact they will have. The more you try to avoid them, the more impossible they become to avoid.

This sense of “the Shadow” can be applied at any level—to society as a whole, to groups or organizations, and to the individual. And we’ll talk about all of the above.

While Carl Jung coined the term, the concept of the shadow is an archetype—it transcends time, history, and culture.

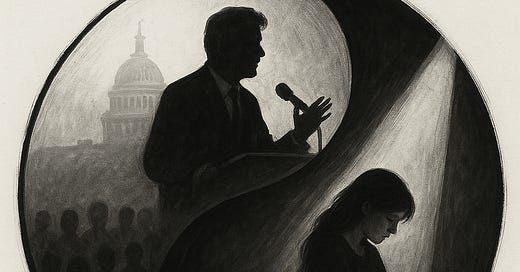

Most of us can picture the “Yin-Yang” symbol. It was a hot accessory in the 1990s (a period that will remain relevant to this topic), but its roots are ancient. The earliest written references to Yin and Yang appear in the I Ching (the Book of Changes) in the 9th century BCE. In Daoist philosophy, it refers to the interdependence of the dark and the light. The dot of black inside the white, and the dot of white inside the black, represent that you cannot have one without the other.

If Chinese philosophy doesn’t feel applicable to you, how about the story of Adam and Eve?

In Genesis, Adam and Eve are in the Garden of Eden. They are naked and unashamed. This is the light—shining brightly, nothing to hide, everything out in the open. But when Eve takes a bite of the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge—the “original sin”—the first thing she feels is: I’m naked. Shame and vulnerability set in, and she covers herself with fig leaves. This, too, is the archetypal energy of the Shadow.

Stories of the shadow—of the dance (or the struggle, depending on how much you resist) between light and dark—are woven throughout time.

And the Democratic Party is no exception.

But let’s start with the country as a whole...

The United States was founded on the principles of freedom and liberation. That man should not be ruled by another man, but have the liberty to rule themselves. To select their own leaders. Our country was founded on the basis of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

But we all know that “all men are created equal” did not apply to everyone. Just as, according to the Old Testament, Eve’s thirst for knowledge condemned humanity from euphoric heaven to a more painful human experience, the “original sin” of our nation was the capture, torture, and forced labor of Africans in chattel slavery.

And that doesn’t begin to account for the sin of slaughtering the Indigenous peoples who already called this land home. Or the denial of equal rights to women.

In his book My Grandmother’s Hands, author Resmaa Menakem raises a powerful question: “How could these settlers be so desensitized to the harm they caused?” He points not just to high taxes on tea, but to the brutal white-on-white depravity the settlers were escaping in Europe—torture and execution as public entertainment, women burned at the stake, people punished simply for wanting to practice a religion other than the King’s.

When we consider what we now know about generational trauma and epigenetics, it makes sense. If your life involved witnessing the torture or murder of your family, especially for something like faith or difference, a numbness to others’ pain could be inherited. Pain and brutality—and hoping it happens to someone else instead of you—was the only life many of them knew.

In my opinion, that’s a surprisingly compassionate lens through which to view the atrocity of slavery. But two wrongs—or a few centuries of wrongs—don’t make a right.

So if those of us in the Democratic Party can agree on anything, it’s that we’ve been on shaky ground from the start.

So let’s focus in. Let’s talk about Monica Lewinsky.

In January of 1998, I was probably wearing a yin-yang symbol on a black cord necklace—or maybe a yin-yang patch on my backpack. I was 15 years old and a freshman in high school. I remember blushing in our Journalism Room, working on the school newspaper, as a sophomore boy I had a crush on read aloud from the Ken Starr report about President Bill Clinton and 22-year-old intern Monica Lewinsky.

Wide-eyed and still innocent, the report described acts I hadn’t known were possible, things I had never contemplated. President Clinton famously said on January 26, 1998:

“I did not have sexual relations with that woman (SHE WAS 22!!!!!), Miss Lewinsky.”

I didn’t understand the context or implications at the time. And the report itself was the most pornographic content I’d ever been exposed to. Between my crush reading it aloud and the natural sexual curiosity of a teenager, I didn’t understand how my body was responding—with shame and arousal—but I had one clear takeaway:

Monica Lewinsky was bad.

I never could have known that just over seven years later, at age 22 myself, a Democratic politician more than twice my age would relentlessly barge his way into my life and my home. I wasn’t thinking about Monica Lewinsky at the time. That’s not how our nervous systems work. I was thinking about survival: How do I get through this?

But the shame was already inherent. It had been absorbed into the shadow of my psyche—and our collective conscience—before I had ever developed a serious interest in politics.

That shame was never righted. Never addressed by the Democratic Party. While we eagerly point out the impropriety of Republican politicians or judges… while we hungrily ate popcorn and claimed to “support women” during the #MeToo movement that exploded in Trump’s first term… when it comes to our own Party, we circle the wagons. The women who share their stories of harassment and assault within Democratic politics are dismissed as “crazy” or “broken.” Their allies? Iced out.

That’s why these issues, banned to “the Shadow,” continue to haunt the Party.

There’s one way out of this darkness: light. We must look—closely. We must listen to understand, not just to check a box. The longer we avoid it, the more destructive it becomes. And it’s not the victims causing that destruction—it’s the people who refuse to look. Who keep it in the dark.

And—like our nation’s history of slavery and genocide—just because you didn’t cause the darkness doesn’t mean you don’t have a responsibility to bring in the light. This is collective.

Finally, we reach the individual level of this uncomfortable but worthwhile healing practice—shining a light into the darkness of our own lives.

Again, we have to remind ourselves: just because something isn’t our fault, doesn’t mean it isn’t our responsibility.

Much of our personal programming is unconscious. Sometimes it’s messages we learned in childhood: that pink is for girls and blue is for boys. That certain jobs are for men, making women unwelcome. Or the reverse. These are messages we can unlearn.

Some of it is deeper and darker. More repressed. Like the subconscious idea that “Monica Lewinsky is bad” instead of: “Politicians who target young staffers are bad.” Or more accurately:

“Politicians who target young staffers are humans who should seek therapy, not elected office.”

Based on our life experiences—the support we did or didn’t receive, the trauma or hardship we have or haven’t faced—we often carry what Brené Brown calls “stories in our head.” Stories that we are bad. That our value is tied to our popularity. Or productivity. Or job title. These, too, are shadow elements to explore.

When it comes to shadow work, some resources can help. One book I like is The Dark Side of the Light Chasers by Debbie Ford. Therapy helps. Journaling helps. If you’re like me, and you’ve (inadvertently) ended up with lots of shadow… you’ll need all of them.

But it doesn’t stop there.

Soon, I’ll write more about mindfulness. My daily meditation practice—with its constant invitation to treat myself with kindness—has been one of the most powerful tools in “reprogramming” my brain. Away from the murky shadows, and toward the light. Mindfulness helped me become my own biggest cheerleader, instead of my own harshest critic. That internal voice of “it’s okay, it’s normal, it’s human” gave me the courage to sit in the darkness of my shadow without running away.

So if you’re wondering where to start, it’s simple.

Where are things going wrong in your life?

What are you avoiding?

Is there anything you’d rather take a drink than take a closer look at?

Start there.

One final anecdote—one especially relevant to politics. I write this with someone specific (and dear to me) in mind, though the same could be said for me, and for many others.

When it comes to the shadow, we’re not all the same. Some people make it through life relatively unscathed. And while I think everyone has some amount of shadow work to do, not everyone has the same amount.

There are many people whose lives are small and contained—and I don’t mean that as a judgment. They’re born into healthy homes, fall in love, get married, raise children, have grandchildren, and die. A good life, well lived.

But like The Man in the Arena, people who are drawn to politics are often seeking something bigger. More expansive. And it’s rare to be in politics and play it safe. Even for the purest at heart, it can be brutal. Politics is a bloodbath.

There’s a common saying in Jungian circles:

“The brighter the light, the darker the shadow.”

That’s what makes sense of it. The balance between light and dark. And that’s why the people who light up a room—the most charismatic, the ones who inspire loyalty and admiration—like the Bill Clintons of the world—are often the ones with the most lurking in the shadows.

My best advice?

Get ahead of your shadow.

Get ahead of the stories in your head that perpetuate harm.

Avoidance is a trap.

It may not be your fault, but it is your responsibility.

“Politicians who target young staffers are humans who should seek therapy, not elected office.”